By Susan St John –

By underfunding investment in the young we’ve been able to create budget surpluses to be siphoned into the NZ Super Fund at the current rate of nearly $2.5b a year. This has some serious impacts for a lot of families, writes Susan St John.

“Sorry kids” says a father. “I know you don’t have a place to live and you are hungry and getting sick all the time but I have decided to put the money into a treasure chest for you so that at 65 you can have a pension just like grandma. Oh, I forgot to say, there is even less for you today because I have to pay for grandma’s pension too!”

So much for the NZ Super Fund, now with $46 billion sitting inviolate in the strong-room.

By underfunding investment in the young we have ensured many families don’t have enough for even a modest lifestyle. The underfunding enables budget surpluses to be produced that are then siphoned, righteously, into the NZ Super Fund at the current rate of nearly $2.5 billion a year.

Other countries with sovereign wealth funds usually fund these from sales of natural resources, ours comes out of economising on vital social spending.

New Zealand also has one of the least progressive tax systems in the Western world: it imposes income tax on the first dollar earned and an additional 15 percent GST when the after-tax income is spent. Families are taxed twice: first to pay for current superannuitants, many of whom are vastly wealthier than they are themselves, and second, to fund their own New Zealand Superannuation – except it doesn’t. The double taxation contributes to shifting debt to today’s workers, many of whom may, for example, end up with bigger mortgages and more student debt that will then make it harder to save for their own retirement.

Contrary to received wisdom, the Fund does not change the future cost of New Zealand Superannuation by one dollar.

There are two worrying things to say about this. First, the perceptions of what the fund will do are largely wrong. Most people think it is there to pay for the pensions of the babyboomer bulge and will run eventually down to zero.

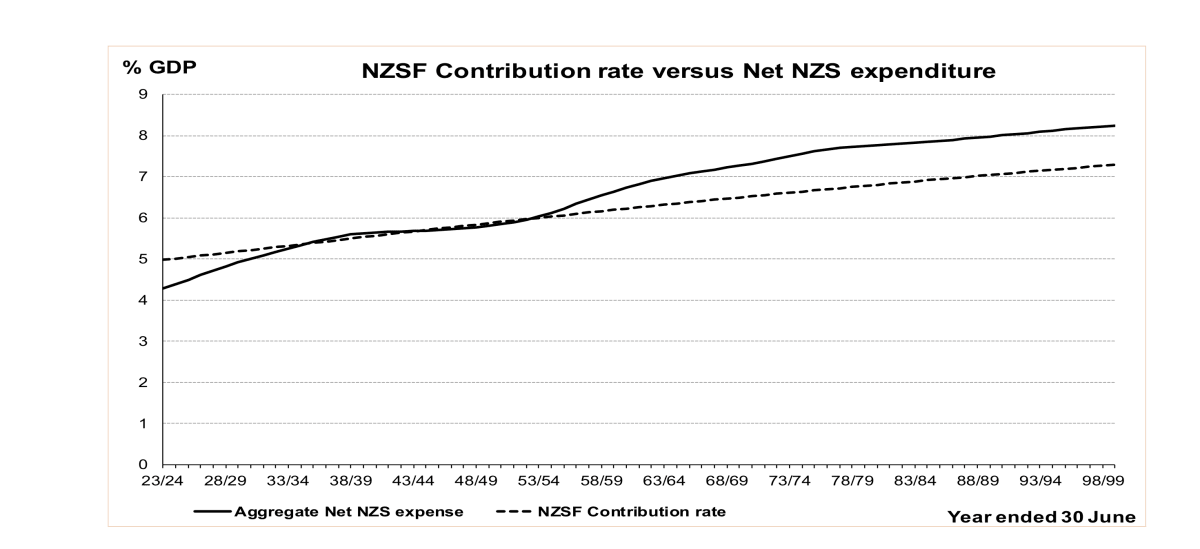

The way it has been set up shows this will not happen. Complex calculations determine each year’s capital contribution to the fund and Treasury’s projections show that withdrawals don’t occur until after 2050. From around the mid-2070s they are only about one percent of GDP, leaving growing proportion of cost still coming from tax. Thus, by the end of the century, withdrawals still fund only about 12 percent of the total cost of NZ Super.

Another myth is that the fund guarantees the current form of pension for future generations. This magical thinking is absurd. No feature of NZ Super: its level, its link to wages, its universality, or the age at which it is paid, can possibly be assured by the fund. The best protection for the future of NZ Super is to reform it so that all citizens understand its function and there is popular support for it because it meets the tests of intergenerational equity and sustainability.

Once the social deficits are overcome and if, and when, there are genuine surpluses, then putting assets on the Crown balance sheet might be supportable. Having a strong balance sheet does not require a ring around these assets so they can never be touched except when a mathematical formula (such as enshrined in the Act) allows for a dribble of a withdrawal.

Furthermore, under the current arrangements, the government does not count the fund’s financial assets against its gross debt when calculating its fiscal targets. If the NZSF assets are netted off (as they should be in logic) net government debt is at chronically low levels. Surely the government should get some credit for saving for a rainy day?

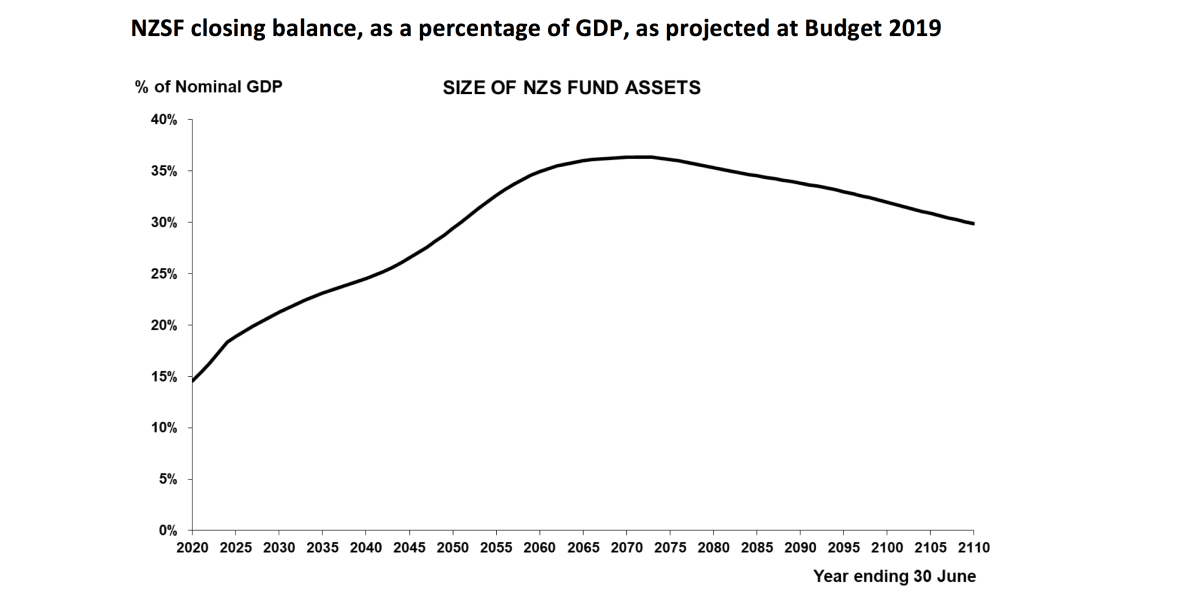

By 2050, when there is a trickle out of the fund at last, all the remaining babyboomers will be 85-105 years old and health-costs will have exploded, squeezing out other spending regardless of the fund. The second Treasury graph shows that the fund doesn’t run down much, even by the end of the century when there will be an enormous stash of paper assets of around 30 percent of GDP. This will be small consolation for the young people of this generation whose needs have been grossly neglected.

* Originally published in Newsroom. Republished with permission.

Susan St John is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Auckland Business School, Director of the Retirement Policy and Research Centre, and a Public Policy Institute Research Associate.