Ko wai te Māori “o waenga”? Te whakaehu ā–mātāwaka, me te mana rite-kore puta noa i ngā uri, te mātāwaka, me te mātauranga ā-iwi

Lara Greaves, Cinnamon Lindsay Latimer, Eileen Li, Logan Hamley, Larissa Renfrew, Andrew Sporle, and Barry Milne – The University of Auckland

Te Whare Marea Tātari Kaupapa are delighted to present our first fully bilingual policy briefing, available in te reo Māori and English.

There is considerable diversity within Māori identities concerning knowledge of whakapapa or descent. Those without knowledge of their whakapapa can have difficulty connecting to both te ao Pākehā and te ao Māori, simultaneously or individually. At the same time, a stronger cultural connection to identity can protect Māori against the impacts of discrimination and buffer against the effects of living in a colonised world.

Identifying demographic differences within diverse Māori identities highlights how ethnic identity labels of Māori relate to sociocultural outcomes. Numbers of those identifying their ethnicity as Māori are lower than those stating they have Māori descent. In contrast, those most strongly identifying as Māori have been more likely to experience discrimination or negative social outcomes. Additionally, those not identifying their iwi or hapū affiliation can be limited in access to cultural and political resources.

Distinguishing the complexity within different Māori definitions of identity is important to policy seeking to reinforce Māori self-determination through mana Māori motuhake (autonomy, self-determination, sovereignty), separate systems for Māori, or kaupapa Māori (Māori approaches or ideology) principles.

Read the key findings and policy implications below, the entire Reo Māori version of the briefing here, and the English version here.

Key Findings

- Of those who did not know their iwi, 6.9% did not identify as Māori. Of those who knew their iwi, 7.2% did not identify as Māori. All of the groups who knew their iwi had higher female representation.

- Those who knew their iwi and identified solely as Māori were on average older than all the other groups. Those who did not know their iwi and identified as Māori and another ethnicity were younger on average.

- The group who did not know their iwi and identified solely as Māori had the highest proportion in the lowest income quintile and the no qualification group. This group had the highest proportion of elementary occupations and plant/machine operators and assemblers, followed by those who knew their iwi and solely identified as Māori.

- Those who knew their iwi but did not identify as Māori had the lowest proportion in the lowest income quartile, highest ratio in the highest income quartile, the university qualifications or above education profiles and at the manager and professionals occupation levels.

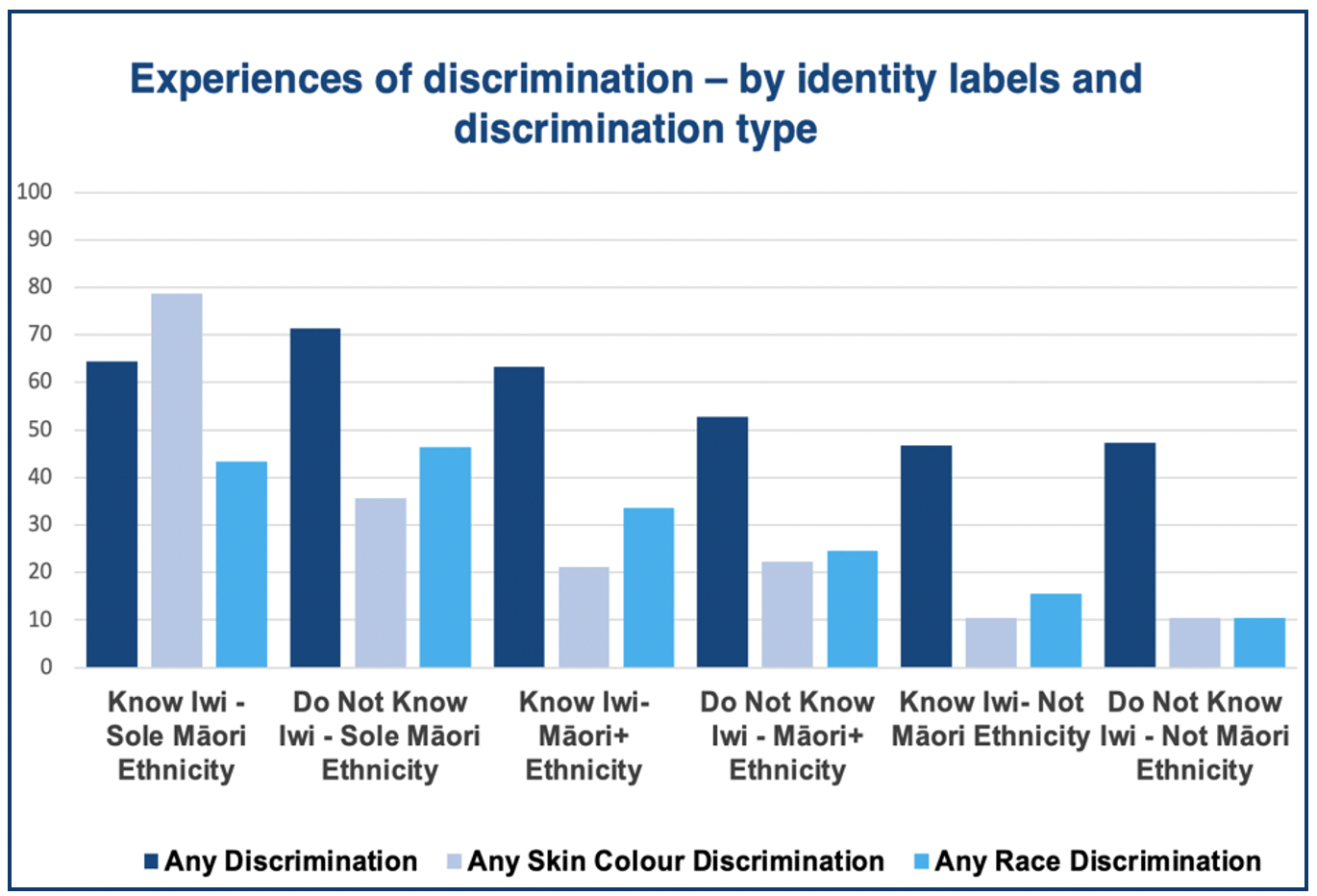

- When tested against the Te Kupenga results, those who did not know their Iwi and identified solely as Māori reported the highest rates of overall discrimination, with those who solely identified as Māori but knew their iwi reporting the highest rates of skin colour discrimination.

- Those who knew their iwi and did not identify their ethnicity as Māori experienced the lowest rates of discrimination, skin colour-based discrimination and race/ethnic group discrimination.

Key Policy Implications

- Policy research and population surveys should seek ways to recognise Māori identity as heterogenous, to tailor approaches to unique and multiple forms of expression.

- Western approaches to identity for policy risk tokenism, undermining the recognition of heterogeneous expressions of Māori identity. Underpinning policy with mātauranga Māori is important for policy aimed at cultural reconnection and Māori self-determination

- Access and guides to the IDI for Māori for policy research for and by Māori are critical to improving understandings of Māori identity for policy

- Increased resourcing for Māori initiatives should be paired with targeted resourcing for sole- identifying Māori who experience the greatest discrimination and racism

- While we showed that many still don’t have whakapapa knowledge, there are limitations to cultural reconnection policies, and they should be used with care as we don’t know the barriers to reconnection. Many advocate for more structural change, rather than focus on cultural reconnection.

- It isn’t clear whether our measures of descent, ethnicity, and Iwi identity are fit for purpose; and measures need state-funded testing for cultural appropriateness, especially across education levels and professions