How we come out of this crisis will depend on how well we are able to imagine new futures, and turn those visions into reality. In this first part of a two-part series on vision-making, Jess Berentson-Shaw looks at what sets apart an effective vision that can lead to concrete change

It was Milton Friedman who captured the current mood of the country, the world really, when he noted that it is the ideas we carry with us into a crisis, or that we push forward from it with, that will determine what happens next.

In the context of Covid-19, there is no shortage of new ideas (and some old ones polished up to look new) being thrust forward to help us develop a vision for what comes next.

Change is in the air. Transformation is not only desirable, but Covid-19 has shown it is necessary in a way the climate and inequality crises for some reason have not. The question that many people ask is, is change possible?

Vision making is about showing that the future is shaped by our collective decision-making now.

Most of us find it hard to imagine a world that is different from what we have now. Facing complex issues in society, many people just can’t see a way out. Partially because many find it hard to see the systems and structures, practices and institutional hierarchies that shape our world and our responses. Rather many people, explain and understand the world in terms of the things they see, smell, touch and taste now. The visible, concrete behaviours and individual choices. Such mental models are a powerful force that cannot be ignored in work that wants to engage with the transformation of systems like policy making, or business practice, or the economy (that most nebulous of entities).

Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel prize for his decades of work uncovering all of the ways our mental processing systems work to protect our existing mental models and beliefs. Explaining that we have a “fast thinking” system that will protect what we already believe for the very pragmatic reason that we cannot stop and relearn everything we have learned every second of every day. It is this system that makes transformation challenging. And it is why vision making is so important. It helps to overcome some of the biases of this ‘fast thinking’ system, it can even engage our second system – the ‘slow thinking’ one.

What is vision making?

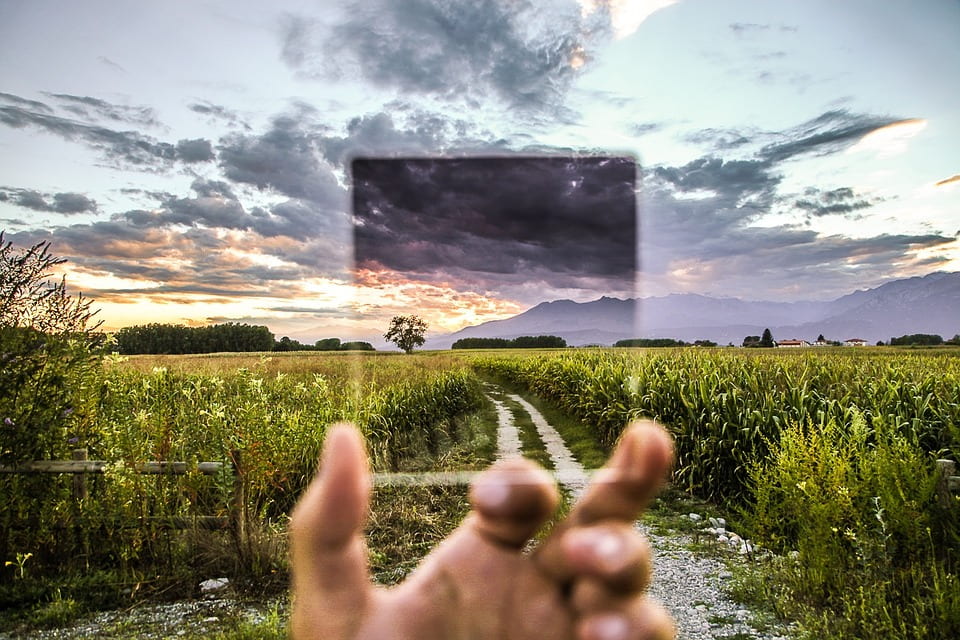

Vision making is the process of imagining a new future, what life would look like if we chose different tracks to travel than the ones we are taking now. It gives people hope and a view to what is possible if we choose to make it so. To see that the future is not inevitable but uniquely shaped by people.

But there is a difference between utopian vision making that people cannot see themselves in or believe is possible (that doesn’t overcome our fast-thinking) and vision making that leads to change. The question is are the visions being set out in our (almost) post -Covid19 world the former or the latter?

… the most effective visions will show people the better world in meaningful concrete ways, lay out a clear process for change and be clear on who can make the change within a system and structure.

What makes an effective vision?

For people doing visioning work, taking account of the research we have on people’s psychology matters; specifically the difficulties people have in seeing the world differently and seeing the systems and structures that shape our response. It will also help vision-makers to understand that particular narratives about how the world works are powerfully embedded in our dominant culture (not all cultures). Dominant narratives (or stories about the world) will uphold and strengthen existing mental models and will drag people back to the status quo. New or alternative visions will need a lot of exercising to become believable.

For these reasons effective vision making needs to:

– Make the imagined real and concrete in terms of people’s everyday lives. How is my everyday life going to look different in ways I can see, small, touch and taste?

– Be clear on the barriers that stop us from reaching this vision.

– Detail the pathways and timeframes to achieve that vision.

– Name the people who have the power to make those changes. The ubiquitous ‘we’ ignores and flattens power dynamics, controlling forces, and decision makers responsibilities.

In other words, the most effective visions will show people the better world in meaningful concrete ways, lay out a clear process for change and be clear on who can make the change within a system and structure.

These are not the only important aspects of impactful vision-making. Next week I will discuss why explicit values-led vision are so important to driving believable change, and how the status quo that vision makers are so enthusiastic about avoiding can be something they end up reinforcing through their vision making processes.

Jess Berentson-Shaw

Jess is the co-director of the Wellington think-tank The Workshop, and a Research Associate at the Public Policy Institute.

Originally published in newsroom. Republished with permission.